By: Roisin Dolliver

Palestine lies on the Great Rift Valley at the crossroads of Africa and Eurasia, a landbridge between the two which is home to five major ecological zones. Despite its small size, Palestine has been home to over 2500 wild plant species, 380 bird species , 91 reptile species and 130 mammal species. This rich biodiversity directly contradicts the terra nullius narrative proposed by the Zionist State, depicting the region as empty, barren, and ownable. Despite the Zionist slogan of “Making the Desert Bloom”, anthropogenic and colonial activities have resulted in 50 percent of the mammals, 20 percent of the local birds, and 30 percent of the country’s reptiles adopting endangered status (Braverman, 2023).

The “Draining the Swamp” project, is an example of the damage the Zionist project has wrought on the Palestinian landscape. Under this scheme the wetland ecosystems of the Huleh Valley were destroyed to create agricultural land. Zionist geographer Yehuda Karmon described the region as “malaria-infested, largely swampy and endangered by floods almost every winter; its people, poverty-stricken and led a wretched life in reed huts and mud hovels”. As Mazin Qumisyeh noted in his 2024 visit to Trinity, “Draining the Swamp”, has resulted in the disappearance of 218 species (Qumsiyeh, 2024).

The Zionist settler state views nature management as a central aspect of their project, claiming that actions taken in the name of environmental protection are apolitical and justifying their operation beyond Israeli territory. Uzi Paz, a founder of Israel’s nature administration states that “The protections [we established] came from the love of nature, without even a drop of politics in it. It was pure and totally clean of such thoughts.” (Braverman). Qumiseyeh, alternatively, claims Nature Reserve boundaries are drawn purposefully to exclude and dispossess Palestinian communities. Critics of the Zionist regime claim the true motivation for Nature Reserve delineation hides in both the strict legislation and regulations that can be imposed on an area once it has been established as a Nature Reserve, and in their strategic placement preventing the development of Palestinian settlements.

Under the Oslo II Accord, the Israeli-occupied West bank was organised into three administrative divisions, Area A, subject to Palestinian authority, Area B administered by both Israel and Palestine and Area C under Israeli authority. Area C comprised 61% of the occupied west bank and the majority of nature reserves and parks, two thirds of which were later declared military firing zones . In 2020, Naftali Bennet, who was the Israeli Defence Minister at the time declared seven new nature reserves and the expansion of twelve others in Area C, around 40% of which were on privately owned Palestinian land. These reserves then come under Israel’s Wild Animal Protection act of 1955 and its Nature and Parks Protection Act of 1998, legal protections which apply even to privately owned land, constraining cultivation and access without compensation. In occupied territories this declaration is made through military order, authorising enforcement from park rangers. The order allows the demolition of any structures built without written permission from the military commander. Ori Linial, the head of Wildlife Trade and Maintenance Supervision Unit and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority (INPA)’s Law Enforcement Division describes the brutal efficiency of military law in the occupied West Bank, boasting “Here, the head of the Civil Administration personally knows all our staff… I would tell him that I wanted to remove a Bedouin neighborhood that was built in my reserve, and he would personally give me the manpower to do that” (Braverman, 2023). Another exemplar of the severity of Israel’s approach to environmental management are the Green Patrol, a special unit of the INPA which does not operate under the police nor answer to them. One of the Green Patrol’s objectives has been to intimidate Bedouin campsites into moving, even by a few meters, to reset the ten year occupation period after which Israeli law stipulates that ownership of land is established (Falah, 1985). They also police “dangerous overgrazing”, by Bedouin flocks under the 1950 Plant Protection Act, which prohibits the grazing of black goats “outside one’s own holdings”.

Another case study is the Wadi Qana valley, also referred to as Nahal Kana. In 1926 the British Administration declared a 7,400 acre forest reserve in the area, followed by the creation of the 3,500 acre “Nahal Kana Nature Reserve” by the Israeli Civil Administration in 1983. The entrance to Wadi Qana is in close proximity to the Jewish Settlement of Karnei Shomron and the Palestinian Village of Deir Istiya, who have used the land for agriculture and recreation for centuries. A baseline study conducted by Qumsiyeh identifies five freshwater springs in the valley, a habitat characterised by mixed Mediterranean forests and red clay soil, and six rare plants not found elsewhere in the West Bank; Overall 253 plant species occur in Wadi Qana, with a particular abundance of Phillyrea latifolia, the green olive tree (Qumsiyeh & Al-Sheikh, 2023).

Braverman describes first-hand the methods employed to dispossess Palestinian residents at Wadi Qana, including constant surveillance, the prohibition of new settlements, demolitions and olive tree uprooting. She spoke to Nazmi Salman, a member of the Deir Istiya council, who described a recent ban on staying overnight in the Wadi. Palestinian families had been ignoring the ban in fear that upon leaving the Wadi they would not be allowed back in. As such they were subject to regular military raids. Movement is monitored in the Wadi by drones and INPA employees. As noted previously, in occupied Nature Reserves, under military order rangers are permitted to demolish any structure not present at the formation of the reserve or built without permission of the military commander. The alteration of any settlement characterises it as a new structure. Salman added a tarp to the roof of his hut, which justified the demolition of the building. Salman also describes how demolition orders, which are supposed to be issued ten days prior to action and subject to appeal, are hidden beneath rocks or behind trees to make them more difficult for farmers to find.

The uprooting of olive trees has been a source of great contention between the INPA and Palestinian residents in the Wadi. The INPA claims that the terrace building, irrigation, ploughing and water resource use of the olive tree planting is damaging to the reserves and other flora and fauna. On one occasion they applied for the uprooting of 1,500 olive trees, which was protested by the tree owners who brought the case to Israel’s High Court of Justice. They protested the allegation that the olive trees were damaging to the landscape, having existed for centuries, and argued that their uprooting was discriminatory when compared to the environmental degradation caused by the licensing of dozens of Jewish permanent structures. The conclusion reached was that only trees under two years of age would be uprooted. However, Palestinian owners claim trees were marked for removal arbitrarily and over 800 were eventually removed. This is one of many instances of uprooting in the Wadi and across Palestine. Overall since 1967 over 2.5 million olive trees have been removed from the West Bank. In addition Palestinian communities have had their access to the Wadi’s springs restricted, and the Jewish presence in the Wadi has been solidified by the marketing of the reserve as an ecotourism destination. Braverman also notes that the entrance to Deir Istiya has on occasion been blocked for weeks in response to alleged rock throwing or tyre burning by its inhabitants. As a final note, the proposed expansion of the separation wall in Wadi Qana would separate the residents of Deir Istiya from their lands in the Wadi, placing those lands on the “Israeli” side.

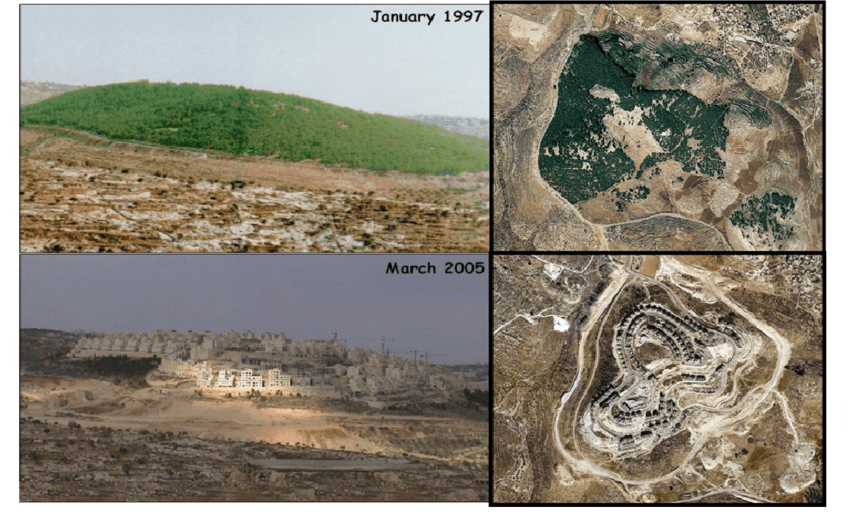

The concept of Nature Reserve delineation to prevent Palestinian development is described by Amro and Najjar, who claim the Israeli government has misused green and open landscape concepts, and their associated planning tools to expropriate Palestinian Lands in East Jerusalem. They posit that to achieve the Zionist ideal of a constant Jewish majority, green areas are declared around Palestinian settlements and later developed into Jewish settlements that prevent the aforementioned Palestinian areas from developing or expanding. They use the example of Abu-Ghneim Mountain, declared a protected green space in January 1997 and developed into the Israeli settlement of Har Homa in 2005 (Amro & Najjar, 2011).

Figure 1: The settlement of Abu-Ghneim Mountain as Har Homa.

Joanna Claire Long similarly suggests that the extensive pine afforestation projects of the Jewish National Funds (JNF) are primarily used to naturalise the Zionist colonisation of Palestine (2005). She posits that the perception of trees as positive additions to an environment was utilised by the JNF to disguise the political nature of their work. The afforestation of Israel has been a key component of the Zionist ideal. Long theorizes that not only do the projects have no true ecological motivations and are the product of ecologically unsustainable green propaganda, but represent active efforts to displace Palestinian settlements and disguise the remnants of those villages destroyed during the 1948 war. She notes the work of Joseph Weitz, the JNF Director of Lands and Afforestation Department from 1932 to 1967. Weitz, a Zionist, has been praised for his establishment of the Yatir Forest, a conifer plantation in an area that receives less than two hundred millilitres of precipitation a year . Weitz believed the success of the Jewish population in Israel was dependent on the complete “transfer” of all Arab communities. In 1940 he wrote, “Amongst ourselves it must be clear that there is no room for both peoples in this country… With Arab transfer the country will be wide open for us” (Long, 2005). During the 1948 war thousands of Palestinans fled to avoid the violence or were expelled by Jewish forces. To capitalise on this exodus and prevent their return Weiz proposed the creation of a “Transfer Committee”, whose purpose was to prevent the return of Arab populations. Long notes that of the 418 villages depopulated and demolished during 1948, only 71 are not tourist and recreation sites managed to some degree by the JNF, and half of these are covered or surrounded by JNF forests. Professor Qumisyeh notes that not only are pine forests poorly suited to the mediterranean environment, but that their acidic leaf detritus prevents the propagation of the undergrowth, and increases risk of forest fires: the JNF disregards this ecological damage in favour of quick growth rates (2024).

Long also discusses that the intensity and defense of the JNF forestry projects are driven by a deep rooted association between the Jewish people and those trees. Many of the forests are dedicated to victims of the Holocaust, and embody both the Jewish history and future. Similarly the Israeli population has come to associate the Palestinian people with “problem species” such as the black goat, camel, olives, and feral dogs. These species are subject to many of the same restrictions imposed on human communities in the Nature reserves, and are targets of confiscation, quarantining, mass poisoning and extermination (Braverman). The Zionist leader Theodor Herzl felt such antipathy to the Palestinian archaeophytes that he praised the idea of “driving the animals together, and throwing a melinite bomb into their midst” in his manifesto, The Jewish State (Braverman, 2023h). The Israeli Plant Protection (Damage by Goats) Law of 1950, more commonly known as the Black Goat Act, limits the number of goats allowed to graze in an area to “one goat per 40 dunams in unirrigated land, and one goat per ten dunamns of irrigated land”. This inhibits the black goat, once ubiquitous with the Palestinian landscape and means of production (Tanous & Eghbariah, 2022). Conservationists praise the ecological benefits of goat grazing for fire prevention. This benefit has now even been recognised by the INPA (Braverman, 2023i). As such the Plant Protection Law has been cast aside, but the damage it caused is not easily reversible.

Other species populations have prospered from biblical associations. The Zionist state sees the return to biblical analogues as another essential step in its formation. As such they have prioritised the reintroduction of species with biblical significance, including the Persian fallow deer, the Asian wild ass, and the Arabian or white oryx. These introductions aim to help connect the Israeli community to their environment and “eliminate from the landscape the former Palestinian presence”, as stated by Palestinian scholar Edward Said (Braverman, 2023n).

The settlers’ approach to environmental management and its role in colonialism is not novel to Palestine-Israel, and is mirrored across history, for instance in the eradication of Bison in North America, another species of great importance to their indigenous community. In 1986 Alfred Crosby coined the term “ecological imperialism”, to express colonisation as a form of environmental terrorism. Concurrent with this idea Qumsiyeh states that the ethnic cleansing of Palestine was not limited to its people but extended to the greater environment and species associated with them. Braverman goes so far as to claim that any form of land management, unless explicitly anti-colonial, runs the risk of supporting its ideal. “Much Western nature management is so entrenched in colonial forms of knowledge and modes of thought that, unless intentionally resisted, its administration innately promotes their underlying structures” (Braverman, 2023e).

The restoration practices undertaken by the Israeli State, particularly in relation to nature reserves, afforestation projects, and the management of protected areas, reveal a complex intersection of environmental conservation and colonial objectives. The Zionist State’s conservation strategies often align with broader political goals, particularly the dispossession of Palestinian communities and the establishment of a settler colonial state. Critics such as Qumsiyeh and Braverman highlight the inherent political motivations behind these conservation practices, emphasizing their role in the broader Zionist project. These efforts reflect a pattern of ecological imperialism, where land management and restoration are not neutral acts but are deeply intertwined with colonialism and the erasure of indigenous presence. Ultimately, the analysis of Israel’s environmental policies underscores the importance of recognizing the political dimensions of conservation and the need for an anti-colonial approach to environmental restoration.

Leave a comment